Just two days before Kent Police responded to a suspicious death and found Ismail S.A. Mohamed dead, naked and with head injuries outside on a Kent hotel parking lot, his sister and parents had tried to convince a Yakima mental health treatment facility and a judge to keep him in custody for treatment.

His family traveled to Washington from their home in Cairo, Egypt several days before the death of Mohamed, 31, a divorced father with two young boys. They came here because his sister reported Mohamed missing on April 14 after he failed to communicate with family members by phone as he typically did.

The family tracked him down at the Bridges evaluation and treatment facility for the mentally ill in Yakima. A Washington State Patrol trooper had found Mohamed asleep and uncooperative in his vehicle along a Yakima street, according to Kent Police. Mohamed was admitted to Bridges on April 16 and discharged on April 17.

Radwa Elfeqi saw a brief story on the Kent Reporter website about her brother’s death on the morning of April 21. He was found at the Crossland Economy Studios hotel. She called the newspaper to say there’s much more to the story than a man being found dead. She wanted the story known so other deaths connected with mental illness could be prevented.

Elfeqi, a psychiatrist in Egypt, wanted people to know the struggles her family faced trying to get help for Mohamed, who she said battled bipolar disorder for years. She had hoped for more help from others in an effort to get treatment.

“What is so hard to believe is we are all subject to this,” Elfeqi said during a recent interview at a local hotel before she and her parents flew back to Egypt, just hours after sending Mohamed’s body home on an earlier flight. “This could happen to you, your brother, your son – how negligent many parties were to save my brother or to be there for my brother is beyond any sensible humanistic brain ability to understand or accept.

“At the (Bridges) hospital, the (Yakima) county court, the law that handles mental health issues. The hotel staff. The neighbors who relied on the hotel to call 911 instead of calling themselves. The police officer who answered me coldly that it is not a felony to not call 911.”

When Mohamed’s family tried to get him to stay at the hotel they were at across town in Kent, Mohamed told them he wanted to remain at the Crossland Economy Studios on Pacific Highway on the West Hill, where he had stayed since February after he moved to town from California. Elfeqi and her parents asked hotel staff and neighbors to call them or even 911 if any problems came up with Mohamed.

“This is a story of a great man who died due to negligence and dismissal,” his sister said. “He was great and gifted. People we lose who are gifted, we need to change society and its flaws. When we dismiss and lose vulnerable people who are gifted, we lose the humanity of society.”

When told details about Mohamed’s death, Ron Honberg, legal director for the Virginia-based National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization, wasn’t too surprised.

“This sounds unfortunately like an all too common scenario not only in Washington state but around the country,” Honberg said during a phone interview. “We have a perfect storm. There’s been a reduction of inpatient beds at hospitals and, at the same time, we are not seeing the development of community services. That is why so many people with mental illness fall through the cracks.

“It’s a real problem, a real dilemma. I hear stories like this all the time.”

Body found

Kent Police responded to the incident because Mohamed was naked and had obvious head trauma, according to police spokeswoman Melanie Robinson. Detective Angie Galetti and another detective investigated the case, which they closed shortly after looking into the details.

“It’s been concluded that Mohamed either jumped or fell from the third story of Crosslands,” Galetti said in an email. “It was reported by other guests that he’d been acting erratically the previous day.”

Mohamed, who had lived at the extended-stay hotel since Feb. 17, reportedly had been spotted by neighbors climbing naked up on a third-story railing the day before his death. Elfeqi had asked neighbors and hotel staff to call her or 911 about such incidents, but she or police didn’t get any calls.

“They let him be,” his sister said. “He tried to climb the railing on the balcony and went back to his room.”

The next night, Mohamed went up on the railing again. Elfeqi said she knows he fell to his death and didn’t jump.

“Everybody was negligent to him being in an episode where he is having delusions and hallucinations he is acting upon and this is how he hurt himself by accident,” his sister said. “This is not a suicide.”

The hotel manager said her company, the North Carolina-based Extended Care Hotels chain, doesn’t allow her to talk to the media. She said she would refer questions to her corporate office for possible response but nobody returned a reporter’s message for comment about the incident.

The cause and manner of death of Mohamed are still pending, according to a King County Medical Examiner’s Office spokesman on Tuesday. The examiner’s office identified Mohamed on April 22 as the man found in the hotel parking lot.

Elfeqi said she talked to the medical examiner’s office.

“They told me they endorse that he fell from the balcony, he was not jumping,” Elfeqi said. “They understand given the history of the case, they see possibly it could be acting out on delusion but cannot be definite because that’s not in the scope of what they can say.”

Yakima stop

Mohamed ended up at the Bridges facility after a State Patrol trooper found him asleep and uncooperative in his vehicle alongside a road, detective Galetti said. He was later admitted to the treatment center before getting discharged on April 17 to his family. Elfeqi said her brother had been found naked in his car, as he often stripped naked during his bipolar disorder episodes.

His family didn’t want him discharged.

“(Bridges officials) thought he could be released which was a huge mistake,” his sister said. “And they put him on more of a maintenance medication rather than a stronger or more potent anti-psychotic which should be able to abort the active episode he was in.”

The family met with doctors at Bridges.

“We explained his condition and that he should not be released,” Elfeqi said. “They didn’t listen to us. They said the law doesn’t allow them to keep him.”

Elfeqi said her brother was a smart man who knew how to act around doctors to get released from mental health facilities. She said he had been in and out of treatment centers while he lived in California for about eight years after moving there from Egypt to study sound engineering.

“He knew what to say,” she said. “He was so frequently detained in the U.S., he knew what to say.”

It frustrated Elfeqi that American law so strongly protects individual rights.

“The law does not protect mental patients at all,” she said.

Mohamed’s family tried to get a Yakima judge to stop his release from Bridges, but that effort failed as well. Elfequi said the prosector and judge told them they understood the family’s concerns but couldn’t keep Mohamed confined if a doctor didn’t classify him as being delusional.

The Legislature in April passed a new law, referred to as Joel’s Law, to go into effect 90 days after the session ends, that gives relatives a chance to keep someone with mental illness committed to a facility.

Under Senate Bill 5269, relatives of mentally ill individuals who pose a threat to themselves or others would be able to petition the courts for involuntary commitment. The bill is named after Joel Reuter, who was fatally shot by Seattle police in 2013 during a bipolar disorder episode just weeks after being discharged from the hospital. Washington is one of seven states that currently prevents family members from petitioning the courts to review mental-health-commitment determinations after a designated mental health professional decides not to detain a person.

Tim Shields, director of evaluation and treatment facilities at Bridges in Yakima, did not return phone messages and voicemails for comment about the case.

Honberg, from NAMI, said he didn’t know enough specifics about Mohamed’s case, but many factors go into whether someone is treated.

“There are a host of factors,” he said. “And it’s hard to treat someone against their will. We place a lot of emphasis on civil rights if you don’t want to be treated. But we are trying to build a community-based system of care, programs and services that have proven effective to give support.”

Many people do live and do well despite having bipolar disorder.

“With the proper treatment, you can recover,” Honberg said. “I know people with bipolar disorder who are doing really well. But you have to manage the illness just like you have to do with diabetes or other illnesses.”

The family of Mohamed is considering whether to file any lawsuits.

“We are looking for contingency lawyers interested in taking the case of my brother, we have very strong negligence of him being released when he needed to be treated and detained,” Elfeqi said.

The brother

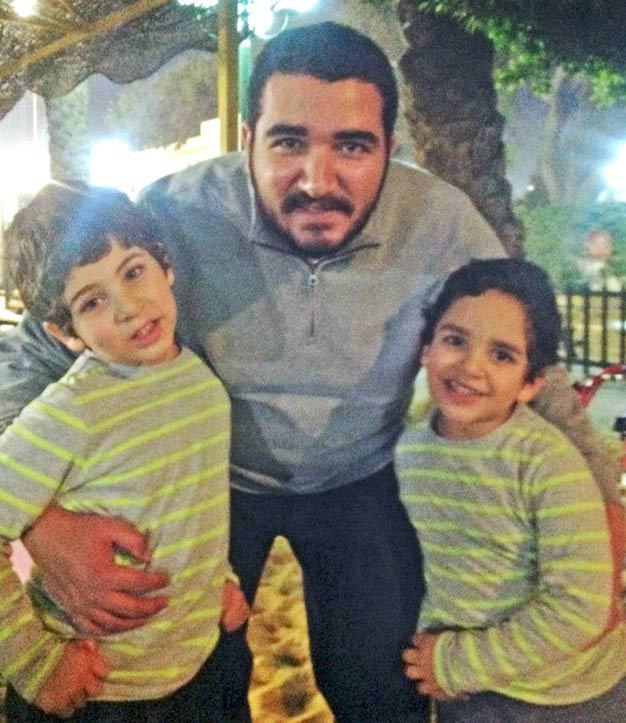

Ismail Mohamed, whose father is a psychiatrist and mother a pediatrician in Egypt, moved to California from Egypt about eight years ago to study sound engineering in the San Francisco area and later in Southern California, his sister said. He got married, had two children but later became divorced. His wife and two boys, ages 6 and 4, live in Egypt.

He moved to Kent from California for a chance at more job opportunities. He worked various jobs, most recently in retail sales in Kent, his sister said.

“He was super smart if it was not to being incapacitated so frequently by the illness,” Elfeqi said. “He did mostly sales. Lately, he was doing retail business – I think on commission basis. He was trying to raise money so his wife would allow him to see his kids.”

Mohamed also loved music and wrote songs. His sister’s Facebook page includes a video of her brother singing. He spoke and wrote fluent English. His family found writings in his hotel room telling about his desire to work and to go see a doctor as he collected his thoughts.

His sister said they wanted him to stay at their Kent hotel rather than Crossland after returning from Yakima, but he had stayed there for a couple of months and felt more comfortable staying in his own room.

“We brought him back to Kent but he did not sleep over with us in our hotel,” Elfeqi said. “He was insisting he needed to get back to work and he wanted to be left alone and focused….We knew he was not doing well, blocking his thoughts. The doctors said he was blocking thoughts but dismissed the fact he could be harmful to himself. This is what we were so worried about.”

His sister and parents visited him at the hotel, but didn’t stay there, which Elfeqi regrets, although they had hoped hotel staff or neighbors would report any problems.

“He was alone in that hotel room when we left him,” she said.

She holds on to many fond memories of her brother and his accomplishments.

“He was brilliant,” she said. “He was a composer. He was a fifth-year medical student in Egypt. He worked with hearing aids and people suffering from tinnitus.”

It’s been a difficult loss for his family.

“We still cannot believe he is gone,” his sister said. “Our tears do not dry…. He is my only younger brother, and only son to my parents. He was warm, kind and exceptional is so many ways. It is not a crime to suffer from a mood disorder. Ismail did not deserve what happened to him nor my family. We went into a major trauma.”

Mental illness in society

Elfeqi hopes by sharing her brother’s story improvements will be made about how mental illness is treated in America.

“Maybe this happened for a higher cause,” she said. “We want to prevent other people from dying the same way.”

Every year, 2.9 percent of the U.S. population is diagnosed with bipolar disorder, with nearly 83 percent of cases being classified as severe, according to NAMI. Bipolar disorder affects men and women equally.

NAMI officials used to grade states on quality of services for the mentally ill, Honberg said. But the group stopped the grading system because no state had really good services.

“With the Great Recession, most state budgets for mental health were decimated,” Honberg said. “And most have not recovered to the point they were before the recession.”

Honberg said an estimated 2 million people with serious mental illness are booked into American jails each year, making up about 20 percent of the jail population. He said most of these individuals are not violent criminals but rather in need of quality mental health treatment and supports.

And about one-third of the estimated 300,000 homeless in the United States are dealing with mental illness, he said.

Ismail Mohamed wasn’t homeless. He wasn’t in jail. But he constantly struggled with bipolar disorder. And his sister believes a lack of proper treatment helped lead to his death.

“It could be any one of us,” she said. “What happens to you is you become a burden. They let you out and you can die. This system pushes you to madness.

“My brother was killed because of the negligence of human beings. Maybe we can save other people.”

• What is bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a chronic mental illness that causes dramatic shifts in a person’s mood, energy and ability to think clearly. People with bipolar have high and low moods, known as mania and depression, which differ from the typical ups and downs most people experience. If left untreated, the symptoms usually get worse. However, with a strong lifestyle that includes self-management and a good treatment plan, many people live well with the condition.

People living with bipolar may experience extreme pleasure-seeking or risk-taking behaviors. Although bipolar disorder can occur at any point in life, the average age of onset is 25.

– Source: The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). See more at: nami.org.

Talk to us

Please share your story tips by emailing editor@kentreporter.com.

To share your opinion for publication, submit a letter through our website https://www.kentreporter.com/submit-letter/. Include your name, address and daytime phone number. (We’ll only publish your name and hometown.) Please keep letters to 300 words or less.